I’m moderating the following Zoom event for SciArt Santa Fe today.

While we as a nation were preparing for the moon shot (50th anniversary today), Fuller was thinking about women’s role in the future. Here’s a link from his essay from 1968, “Why Women Will Rule the World,” published in McCall’s magazine. He got some things right (women as global leaders) and some things wrong! (increasing nudity). Oh well!

The “City Different’s” folk art museum on Museum Hill is a popular destination. Its rooms are chock full of materials affording colors, textures, craft techniques, and little narratives in dioramas and retablos with amazing detail. The cornucopia of collectibles is partly due to the fact that the museum is the repository of the massive “folk art” collections of “mid-century modern” designer Alexander Girard, who designed the display of his collection in the museum as a labyrinthine, near immersive experience.

Important as that is, that exhibition does not solely represent the mission of the museum. One can understand the dilemma: the modern-era concept of “folk art” is a colonializing one, something that Girard, from his mid-century viewpoint, probably could not appreciate. For all the brilliance of the designer–and the museum also has an exhibition of his own career from his days as head of Textile Design for Herman Miller to his work as house designer for Braniff Airways–his interest in dolls and parades and their paraphernalia supports what today might be considered a somewhat infantalizing, old-school approach to “other cultures.”

But the museum is also a member of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience (www.sitesofconscience.org), a network of global sites, institutions, and memory initiatives that “connect past struggles with today’s movements for human rights.” For many indigenous cultures–historically those cultures provide us with the authentic, craft-intensive folk art that everyone loves–are also cultures that have been marginalized or even under erasure by rapidly urbanizing nations in what we used to call the “third world.”

The Museum of International Folk Art has several other small exhibitions that support a recognizable global trend on the part of formerly oppressed people, or people forcibly assimilated to the demands of economic development and modern urban environments, to reclaim their original crafts as forms of resistance.

An example is the exhibition, “Crafting Memory: The Art of Community in Peru,” which focuses on the plight of migrants: people forced for economic. political, or environmental reasons to leave their ancestral communities and who are denigrated in the city. For example, the signature Peruvian wool hat called the chulla and the full skirts called polleras typify traditional dress that stigmatized their wearers, who were derided as “chola” or “cholo,” an ethnic slur. Qarla Quispe, a young artist working in Lima, creates defiant polleras from potato sacks or prints with contemporary graphics to tell the stories of the wearer’s family. She is part of a movement of artists who mix old cultural traditions with new. They are paired in the museum with T-shirts by Peruvian

collective AMAPOLAY, which combines urban immigrant street graphics with motifs from the Andean highlands, a mixture of tribal and urban called chicha (from the popular music style named for a type of beer). The shirts raise awareness regarding the plight of migrant cultures.

The chullo, the colorful knitted hat with ear flaps worn by young men who reach maturity in the Andes is revived by Aymar Ccopacatty, an Aymara artist, who knits a gargantuan version out of the plastic bags that litter Peruvian cities today–a critique

of the consequences of modernization. The chullo were individually crafted by fathers for their sons and became part of their identity, but also became a symbol of migrants’ tribal origins that helped make them targets. The late twentieth century saw violent cultural changes in Peru during the twenty-year conflict between the military and paramilitary, and the forces of the Maoist Shining Path. Towns were decimated across the map and the particular victims were the rural poor. More than 70,000 inhabitants disappeared. One story has it that the chullo could help a grieving family identify a body otherwise too disfigured or decayed. The refuse plastic fabric of Ccopacatty’s sculpture reflects that history but also speaks of the disfigurement of traditional ways of life and the deterioration of the Peruvian land.

“Sights of Memory: The Art of Community in Peru” is curated by Amy Groleau. It opened in 2017 and closes July 17, 2019.

Minna White is the creator of rugs, wall hangings, and other textiles made with a felting process that combines wool from different colored sheep into organic, abstract designs recalling Kandinsky or Miro.

I visited her studio with a beautiful view in El Prado near Taos, where she works with long-haired out coats of the Navajo-Churro, or Churro, sheep, a breed that was brought to North America in the 16th century by Spanish colonists. The sheep can be black, white, a variety of browns and grays, even striped. White does not dye the wool but cards it and uses the natural colors in a felting process to create her soft, thick textiles.

Her process can be found here:

An exhibition of artists’ reactions to wars–all wars–is on view in the small but beautiful gallery at the Nick Salazar Center for the Arts, Northern New Mexico College in Española. The show’s presence in that historic town north of Santa Fe and south of Taos reflects the high toll wars have on small communities all across the nation. Proportionately, the losses and the survivors’ stories of suffering hit these small communities harder. Nearly half the soldiers who fought the Iraq War, for example, came from communities (like Española) with populations under 25,000 (NPR “Morning Edition Feb. 20, 2007)

“After War: How War Affects Community” is curated by Sabra Moore as part of a series of exhibitions entitled “Visible Confluences. Moore wanted to include the notion of “all wars,” despite the show’s small size. Films by Cynthia Jeanette Gomez, David Lindblom, and Daniel Valerio express the experiences of the descendants of Genizaros (Native American slaves who often won their freedom fighting on the frontier). Julie Wagner shows a 60-year-old Japanese album full of ink drawings referencing aftermath of Hiroshima, and replicas of those drawings.

Julie Wagner, “Pines by the River” (book, 2006) and “Survivors” (ink drawings on the wall, 2018).

Margaret Randell’s photos show citizens visiting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. to find the names of those lost, and Nicolas Herrara paints about military experiences during the Iraq War. Moore herself shows multivalent works in the form of houses or boxes that tell stories. Norma Navarro weaves fiber art to convey the tearing apart and reweaving of communities. And Dana Chodzko shows twisted branches that poetically express the effects of PTSD, the result of any war.

Sabra Moore, Roger Mignon (far right) and one other stand in front of Moore’s “Story Scrolls House” (2018); Margaret Randall’s photos of the Vietnam War Memorial (1985) on wall.

NNMC Gallery view showing Moore’s “How Do We Get Out of the Box” (front: cedar poles and mixed media, 2005); on wall: Nicolas Herrera’s “The Eye of the World” (2003) and Dana Chodzko’s wall sculptures made of roots and branches.

The exhibition went up August 24 and can be viewed through September 21, 2018.

My first Santa Fe Indian Market since taking up full-time residence in this city. Some beautiful work alongside a what I would have to call tourist art. Given the challenges and conflicts facing First Nation peoples of late, I had to wonder, where is the political commentary here? “It doesn’t sell very well” I was told, again and again, by the vendors. But one glaring exception was the Market’s Blue Ribbon winner in the Contemporary Dress category (VI, Division D).

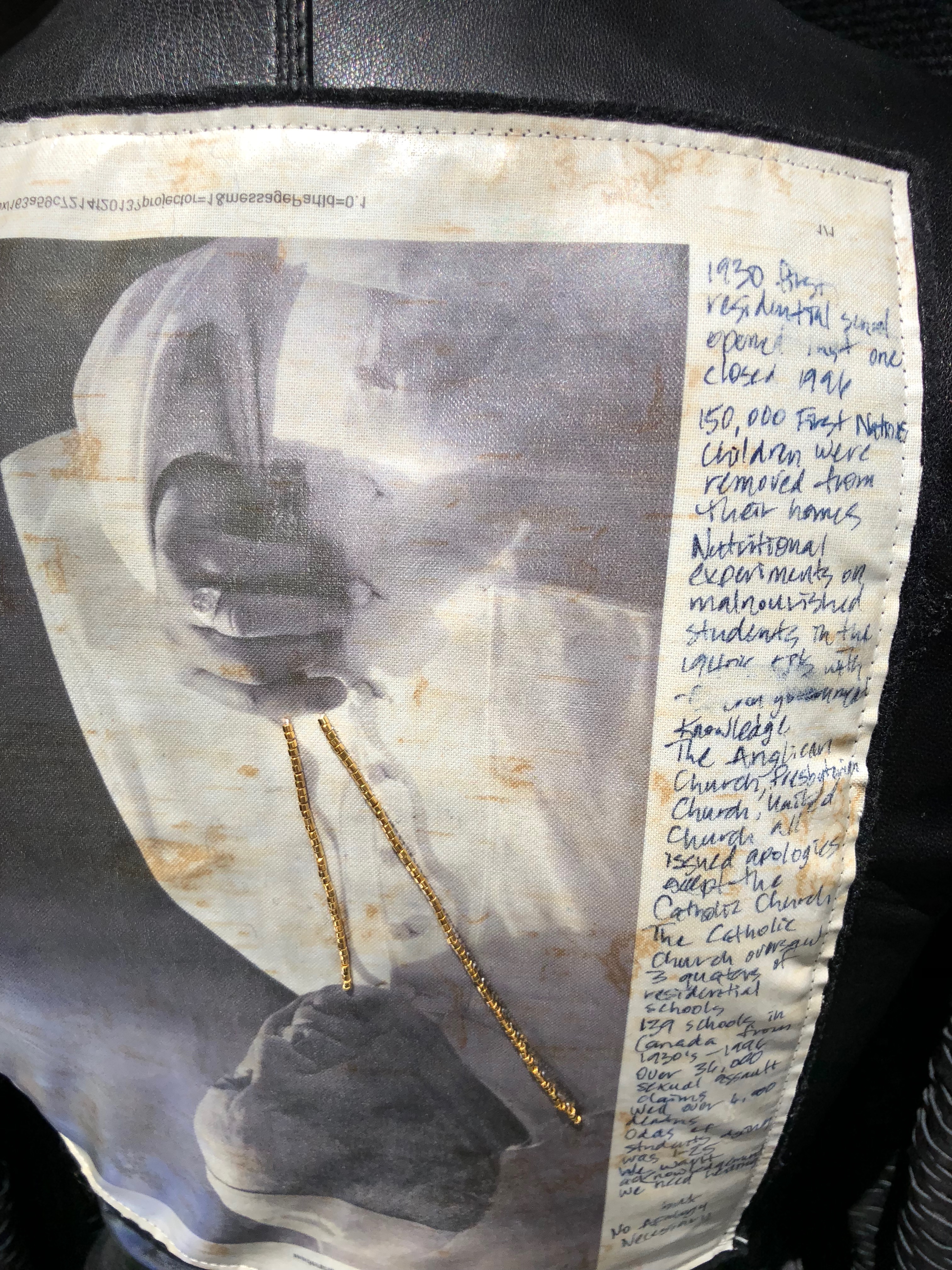

First Nation fashion designer from Vancouver, Canada, Sho Sho Esquiro (Kaska Dena and Cree) presented her work, “No Apology Necessary,” a black leather jacket with openwork, lattice sleeves. A photo of the Pope appears upside-down, emblazoned on the back of the jacket alongside a handwritten “letter to Pope Francis,” a story told first-hand about the “residential schools” run by the Catholic Church in Canada from 1930 through the 1990s. Children were forced from their communities to attend the schools–essentially they were kidnapped–under a policy known as “aggressive assimilation.” The designer’s father was a residential school survivor. The children were isolated from their parents and frequently abused. By 2007 the government apologized and even compensated some of the former students. Most churches that ran schools also apologized. But the Catholic Church, which ran most of the schools, did not. Esquiro’s “No Apology Necessary” makes the point that those affected by the legacy of residential schools know they will never hear an apology and First Nation people should not waste their time expecting one. The traumatized heal themselves.

Sho Sho Esquiro has shown at New York Fashion Week, Jessica Mihn Anhs Fashion Phenomenon in Paris, and at venues throughout Canada and the U.S. She uses materials native to northern Canada like skins, furs, shells, and bead work. In “No Apology Necessary, the Pope holds a real strand of 14K gold beads (Esquiro is also from the Yukon), referencing the riches of the Papacy.

I will miss you.

Spring 2018

This course considered the zombie in popular media as metaphor for the impact of neoliberalism on artists and the populations they serve.

Review of Gregory Sholette’s Delirium and Resistance: Art and the Crisis of Capitalism. Forward by Lucy R. Lippard. Ed. by Kim Charnley. London: Pluto Press, 2017.

Delirium and Resistance is an abstract title, inscribed on an abstract book cover. The restless reader might hastily judge it as just one more theoretical tome in the vast sea of perspectives on crises in art today. But appearances are deceiving. Gregory Sholette’s new book intends to splash cold water in the face of aesthetic narcosis. It’s like Alice came upon a mushroom marked “Eat Me” that, when consumed, eradicated Wonderland, or at least made it into a house of cards observable from the outside. Some of us might not want to awaken from our opioid aesthetics (our neoliberal delirium) or embrace the possibility of change, hobbled as we are by our addictedness and fear. The author aims to open our eyes, and, when we do, it is remarkable how invigorating our new acuity turns out to be.

Delirium and Resistance (henceforth D&R) is a book of essays Sholette wrote over about twenty years (from 1997 to 2016), but covering movements going back to the 1980s, with references to the 1960s. The book is divided into three sections: “Art World,” “Cities Without Souls,” and “Resistance”—respectively, these deal with art today as a supreme capitalist enterprise, the paradox of artists vs. gentrification in cities, and, finally, the efflorescence of social practice amid a bare art world. D&R builds on the author’s signature concept of artistic dark matter: the ninety-nine percent who support the art industry with tuition, fees, dues, purchases of art materials, and debt, and through their own unremunerated artistic efforts—all amounting to a “missing mass,” while a tiny number of artists and artworks meet with material success.

In making itself known through multitudes of extra-institutional activities, this dark matter ironically illuminates the fully financial phenomenon that is art today—a system of bare art, to use a term borrowed from Giorgio Agamben’s “bare life,” the reduction of life to mere subsistence devoid of agency. With bare art, art is stripped of its rhetorical high ground, its secrets about ineffability, and its charmed lifestyle. It materializes as pure capital. In Sholette’s eyes, we are currently witnessing a fermentation of dark matter activity, a critical moment in which dark matter is becoming visible, even chic, as museums and other art institutions scramble to embrace social practice of all stripes, from performance art to community advocacy and even commonplace activities like cooking.

So, resistance is endangered by the hallucinatory bounties of capitalism, but the bloated system might be reaching a tipping point. Sholette believes that it is, and, if anything is to be gained, we must engage with the efforts of the past, an archive of mostly un- or under-theorized activity, as a resource.

What makes the book significant is not only Sholette’s theoretical acumen, but also his authenticity. Like an emancipated Alice, his perspective draws from both within and without. As an activist and professor of art, Sholette has taken part in a number of key activist art groups since the 1980s, (PAD/D, REPOHistory, Gulf Labor Coalition, and, with Olga Kopenkina, the Ukrainian Imaginary Archive, IA). He witnessed first-hand the disruptions of the streets with Black Lives Matter and Occupy Wall Street, events that involved artists self-exiled from the art world. D&R’s essays were written at different moments in the past decades of activist art in “an attempt at formulating a broader thesis about art as resistance.” (151) That resistance, though atomized in thousands of particular contexts, relentlessly moves its aggregate mass towards liberation from anaesthetizing aesthetics, and eventually, perhaps optimistically, to cracking the code of capitalism itself.

This summer I met up with artist Sabra Moore at Angelina’s Restaurant, with the big chili pepper sign, on Fairview Street just by the Rio Grande in Española. We were about to tour the district elementary schools where she has been working to create permanent tile mosaics created from individual paintings by the school children throughout the rural area. (read more – pdf attached) Ryan-Moore

Students in my Art & Environment class at LSU are getting some ideas on how to approach local communities with environmental hazards. They are tasked with creating social practice projects (and writing analyses of their own works) in Louisiana communities with toxic leaks or waste dumps. We are working with the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN)! https://leanweb.org/

Students in my Art & Environment class at LSU are getting some ideas on how to approach local communities with environmental hazards. They are tasked with creating social practice projects (and writing analyses of their own works) in Louisiana communities with toxic leaks or waste dumps. We are working with the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN)! https://leanweb.org/

Judy Natal is a Chicago-based artist and photography professor at Columbia College Chicago. Her photographs and videos have been exhibited internationally and are in permanent collections around the world. An Archive of her papers, lectures, writings, research and photographs has been established at The Center for Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art and she has received numerous commissions and awards including a Fulbright Travel Grant, Illinois Arts Council, Polaroid Grants and New York Foundation for the Arts Photography Fellowships. Author of EarthWords and Neon Boneyard Las Vegas A-Z, Natal’s photographs explore the visual and textual narratives of landscape. She’s held artist residencies that have taken her to Iceland, the Robotics Institute, Joshua Tree National Park, and in Arizona at Biosphere 2, where she founded an artist residency. Her newest project addressing global warming, The Weather Diaries, has brought her to Iceland and the Faroe Islands – the project works to bring immediacy to the dramatic weather events we are witnessing around the globe

Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World is the inaugural exhibition of the Design Museum, London, in its new quarters in High Street, Kensington. Curated by Justin McGuirk. Happy to join other authors’s works in this catalog. The exhibition closes April 23, 2017.

In a project called Wuyong (“Useless”), to be unveiled at the opening exhibition, “Design and Love” at the new London Design Museum later this month.

Revised “Hyperdressing” essay will be published in the catalog for the great new exhibition “Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World,” opening at the new quarters for The Design Msueum on November 24.

Rather than Hokusai’s The Great Wave–and more interesting–the dress conjures up Fukushima and the tsunami, 5 years ago last week. What’s the connection between advancing technology and rising waters?

@cutecircuit #wearabletech #global warming

The exhibition Coded Couture at Pratt Institute gallery in New York is a great exploration of what is becoming a bigger field–the thoughtful investigation and interrogation of what “wearable technology” is actually capable of. Melissa Coleman’s mind-blowing Holy Dress (with Joachim Rotteveel and Leoni Smelt) is a dress as a gilded cage that delivers a jolt–literally an electric shock–to its wearer based a process of creating narratives monitored by lie detector technology embedded in the piece. Wow. Pain and pleasure.

The electrical charge of this “overdress” creates little light flashes across the dress that my iPhone camera can’t capture. On the mannequin, a programmed array of flashes runs. We have to imagine the shocks.

Review appeared back in November. Textile History is an international, peer reviewed journal.

Ryan.GarmentsofParadise.TextileHistory.11.1.15

Just finished teaching a new course on art and the environment (an art history/contemporary art course). (See courses page for syllabus).

The course subtitle was “Changing Views of Landscape” and we examined the very meaning of the term “landscape”– a term that has long-standing aesthetic subtexts — and landscape painting and photography, which have informed our expectations for our environment.

We read historical texts that contributed to the formation of our landscape ideas by writers like Uvedale Price, Richard Payne Knight, Henry David Thoreau, John Brinkerhoff Jackson, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and all the rest, and explored recent movements like deep ecology and eco-terroism. The overarching perspective from the present were the ecological writings of philosopher Timothy Morton, especially his book Hyperobjects (U. Minn. 2013)

Students used historical, aesthetic, and ethical discussions to ground their own community-engagement projects addressing clean air and water issues and how people deal with them. Below are some links to the class projects.

Environmental Justice Now

https://www.facebook.com/environmentaljusticenow/

WAC Water

https://wacwater.wordpress.com/

Losing Louisiana: A Memorial Service for New Orleans

https://www.facebook.com/losinglouisiana/

Breathe225

At the Lively Objects Opening, Museum of Vancouver @ISEA2015

It was worn by Boris Kourtoukov of the Social Body Lab http://socialbodylab.com

Monarch is a harness with wing-like shoulder enhancements that render the wearer more fearsome. The structures expand and contract in response to sensors on the arm reading muscle movement so they mimic a “fight or flight” posturing. It is an example of an expressive wearable that addresses human interactions and public display, not just (like so much wearable tech) online communication and consumption.

You must be logged in to post a comment.